[This

is adapted from an excerpt of my book You

Can Write for Children: How to

Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers.]

It's

tempting for authors of historical fiction to go on at length about the time

and place where their book is set. After all, it's fascinating to them, and they did all that research!

But for readers, especially children who may not have a particular interest in

the era portrayed, daily life should be shown in action instead of pausing the

story to explain the history.

Life

has gotten more fast-paced, from TV shows and movies to daily activities, which

may be why some older historical novels don't hold up as well. They're too much

about the history, and not enough about a great story. In general, readers

don't care as much about setting as they care as plot and characters. Still, a

strong setting can provide an interesting backdrop for a story and teach young

readers about a different part of the world or the different way some people live

(or lived).

Young

readers will typically enjoy books best if the setting serves as a backdrop

rather than being described in enormous detail. For my Egyptian mystery, The Eyes of Pharaoh, I tried to weave in

details without stopping the plot. The book opens like this:

Seshta

ran. Her feet pounded the hard-packed dirt street. She lengthened her stride

and raised her face to Ra, the sun god. Her ba, the spirit of her soul, sang at

the feel of her legs straining, her chest thumping, her breath racing.

She

sped along the edge of the market, dodging shoppers. A noblewoman in a

transparent white dress skipped out of the way and glared.

In

just a few lines, readers learn the setting (dirt street, market), cultural

details (noblewoman), and religious references (Ra, the ba). But they are all

conveyed within the action, as the main character races toward her goal.

On

occasion, historical fiction writers may want to show an unfamiliar attitude. This

can require a bit more explanation. For example, in my Mayan historical drama, The Well Sacrifice, the narrator

describes her sister like this: “Feather was beautiful even as a child.... Her

dark, slanting eyes were crossed, and her high forehead was flattened back in a

straight line from her long nose.” This shows the different Mayan

interpretation of beauty. Otherwise, a physical description of Feather might

have convinced young readers that she was ugly, rather than beautiful by the

standards of her time.

Still,

to be true to the time and the characters, historical fiction writers have to

trust their readers to notice and interpret shown details. In The Well Sacrifice, I couldn’t explain

that the Maya didn’t have wheeled vehicles, since the Mayan narrator wouldn’t

be aware of what her culture did not have. I could only show them traveling by

foot or canoe. (An author’s note at the end of the book also pointed out this

details. Teachers also may be able to find supplemental material posted on the

author’s website, such as I have

here. Finally, pairing historical fiction and nonfiction can be a great way

to get readers interested in the culture because of the story, while learning

facts through the nonfiction.)

My

philosophy is that people in the past were much the same as people today in

most ways – they were motivated by fear, love, pride, faith, and so forth.

Readers can connect to these motivations and emotions even if the specific situations

are different. That's why young readers can fall in love with books set during

the Civil War, such as Jennifer

Bohnhoff’s The Bent Reed, or on

Java when Krakatoa erupts, such as Sara K Joiner’s

After the Ashes. To them, Suzanne

Morgan Williams’ novel Bull Rider, set only a few years ago, is as

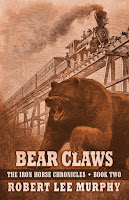

historical as Robert

Lee Murphy’s The Iron Horse Chronicles, set during the westward

expansion of the US, or my novels set in the ancient past. Kids can enjoy time

travel novels such as Louise

Spiegler’s The Jewel and the Key, set in Seattle both in contemporary

times and at the beginning of World War I. Depending on the child, both

settings may be equally exotic.

Chris Eboch writes fiction and nonfiction for all ages, with

several novels for ages nine and up. The Eyes of Pharaoh is an

action-packed mystery set in ancient Egypt. The Genie’s Gift draws on the

mythology of 1001 Arabian Nights to take readers on a

fantasy adventure. In The Well of Sacrifice, a Mayan girl

in ninth-century Guatemala rebels against the High Priest who sacrifices anyone

challenging his power. The Haunted series,

which starts with The Ghost on the Stairs, follows a

brother and sister who travel with their parents’ ghost hunter TV show and try

to help the ghosts while keeping their activities secret from meddling

grownups.

Chris's writing craft books include You

Can Write for Children: How to

Write Great Stories, Articles, and Books for Kids and Teenagers and Advanced Plotting. Learn more at www.chriseboch.com or her Amazon page. Sign

up for her author newsletter for news and

special offers.

No comments:

Post a Comment